Kimberly Burleigh’s Shadow Archetypes Predict the Not-So-Distant Future

By Emilie Trice

Kimberly Burleigh works across stratifications of simulacra. Her art has evolved over the last four decades; from her paintings in the 1980s of the mediated image (first translated via television’s RGB color spectrums in the 1950s and 60s), to her current animations rendered in 3D modeling programs that the artist executes herself— a far cry from many of her contemporaries who outsource the actual work.

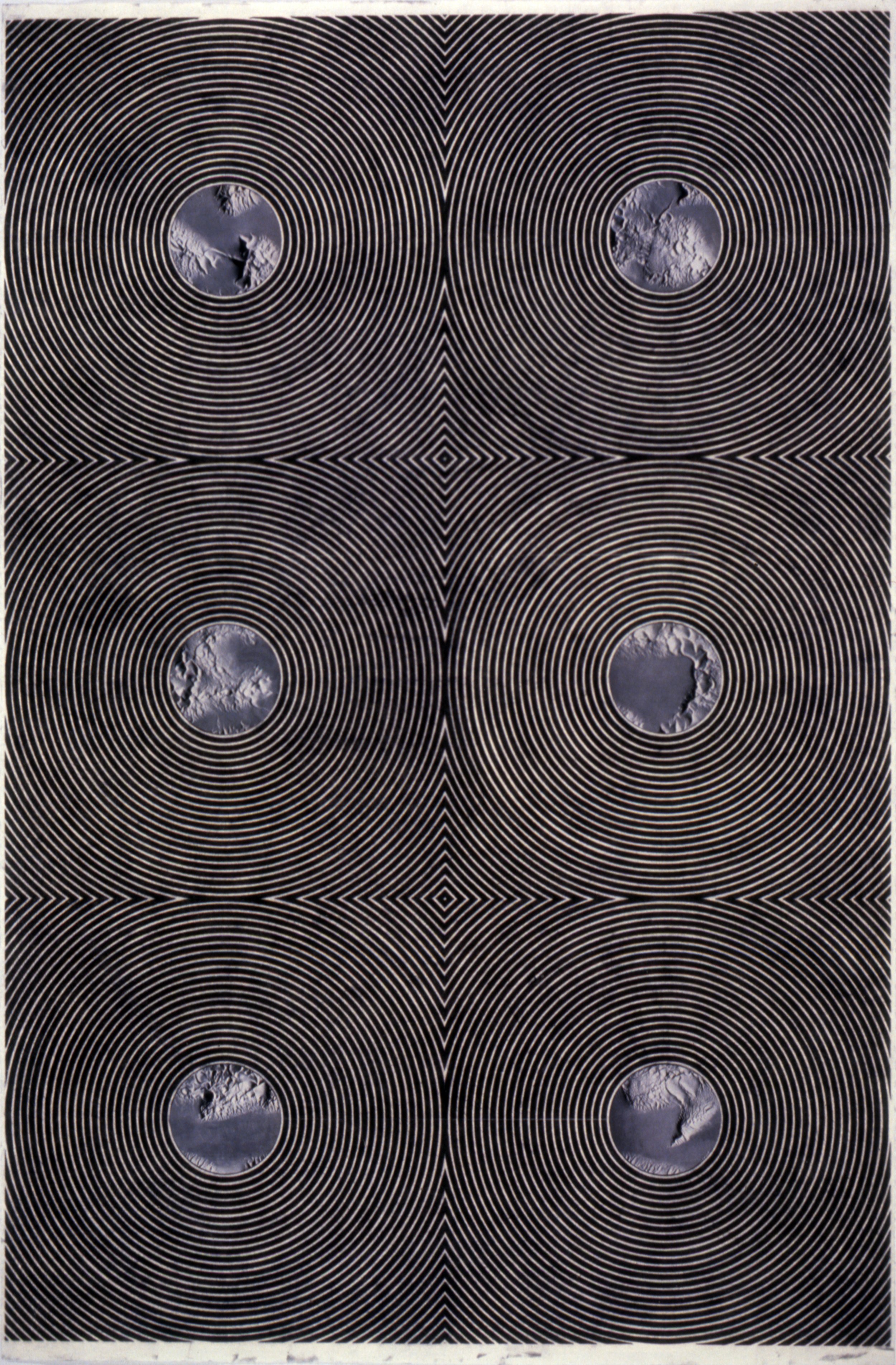

An artist’s artist, Burleigh operates from an almost clairvoyant vantage point that’s only apparent when reading the full arc of her career with the uncanny luxury of hindsight. Two years before 9/11 happened, a touchstone in the US culture-wars, Burleigh was creating “fake” photograms in Maya, a software program that allows you to build a 3D object but render only the shadow.

In her series Digital Images, Burleigh constructs ghostly, ominous still lifes that feel like x-rays, the kind that airport security personnel now scan day-in and day-out with hyper vigilance bordering on paranoia. This was the “before-times,” however; the late 1990s—when the thought of terrorists hijacking a commercial flight with only household boxcutters seemed utterly ludicrous. Burleigh’s imagery somehow managed to wrestle the future, and the past, out of the ether and condense it into a frame.

The artist explains that in this series, she was “harkening back to the early modernists, while also referencing airport surveillance and the conveyor belts that passengers put their objects on to be scanned.”[1] Every shadow-object depicted in the series is actually derived from a terrorist device, such as modern bomb detonators or ancient iron jacks, known as caltrops, that Roman soldiers would place on roads to mame enemy horses and disable advancing armies.

Still, many of her shadow-objects depict ordinary household items, and it’s that uneasy equilibrium—between the mundane everyday and the extraordinarily evil—that piques Burleigh’s interest. Burleigh herself comes across as utterly upbeat: positive and cheerful, agreeable in every sense. Her work, however; mines the darker recesses of the human psyche, and the collective unconscious that Carl Jung hypothesized held the key to mankind’s lingering and morbid fascination with what he termed the “shadow archetype.” [2]

Burleigh identifies her own shadow archetype in society’s obsession with television, exemplified by the popularity of true crime, horror genres, and other cinematic manifestations of thanatos (the unconscious urge to die, also known as a death wish). Despite the prevalence of these psychological and philosophical tenets throughout both ancient and modern history, Burleigh’s interpretation is borderline post-human.

Throughout her career, Burleigh’s art has always invoked the uncanny valley, a term generally applied to artificial intelligence in cyborg form. As an aesthetic theory, the uncanny valley exists when a human-like robot triggers a sense of unease in an actual human, but Burleigh manages to achieve this emotional response through her works that include no figuration at all.

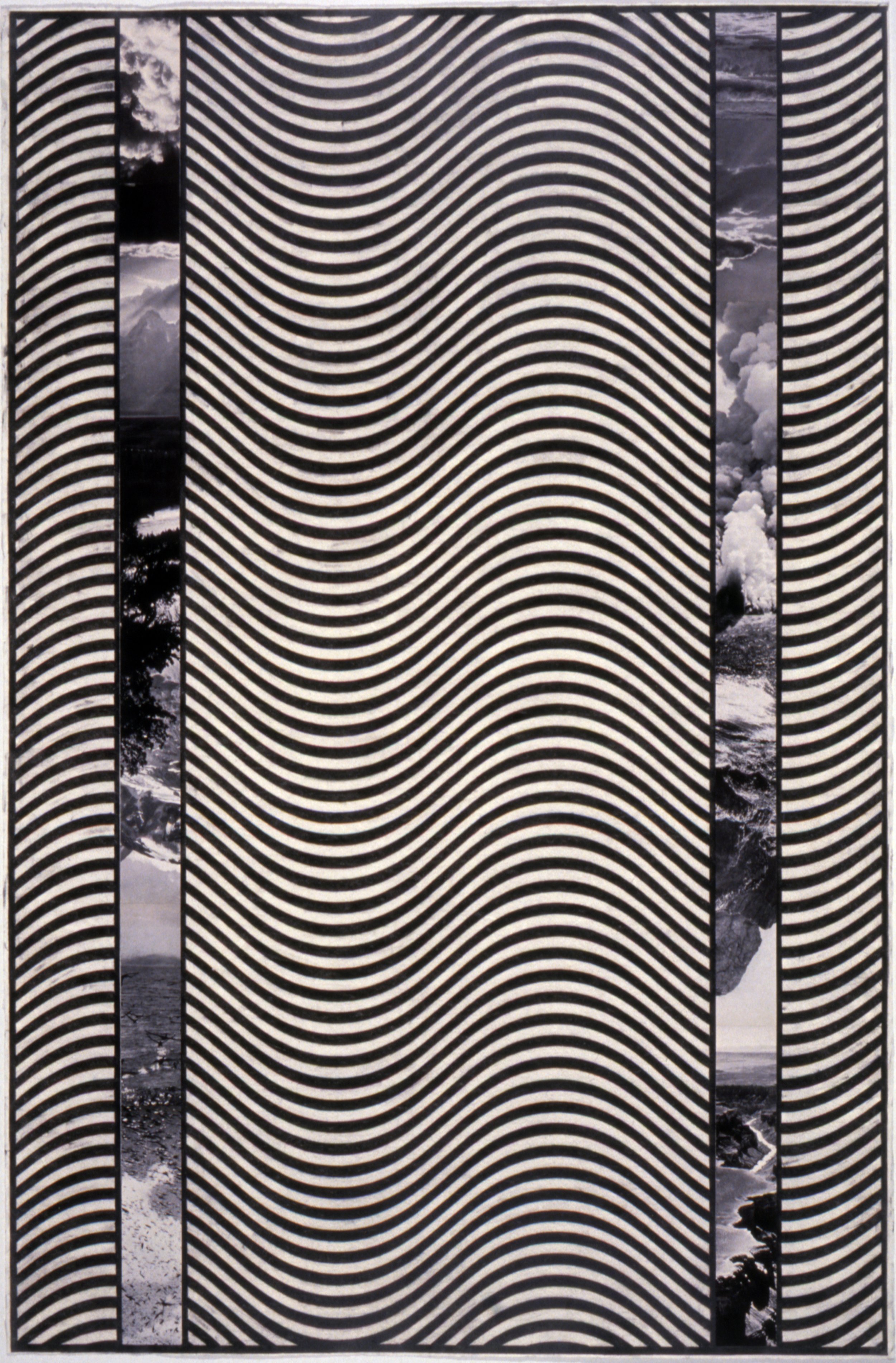

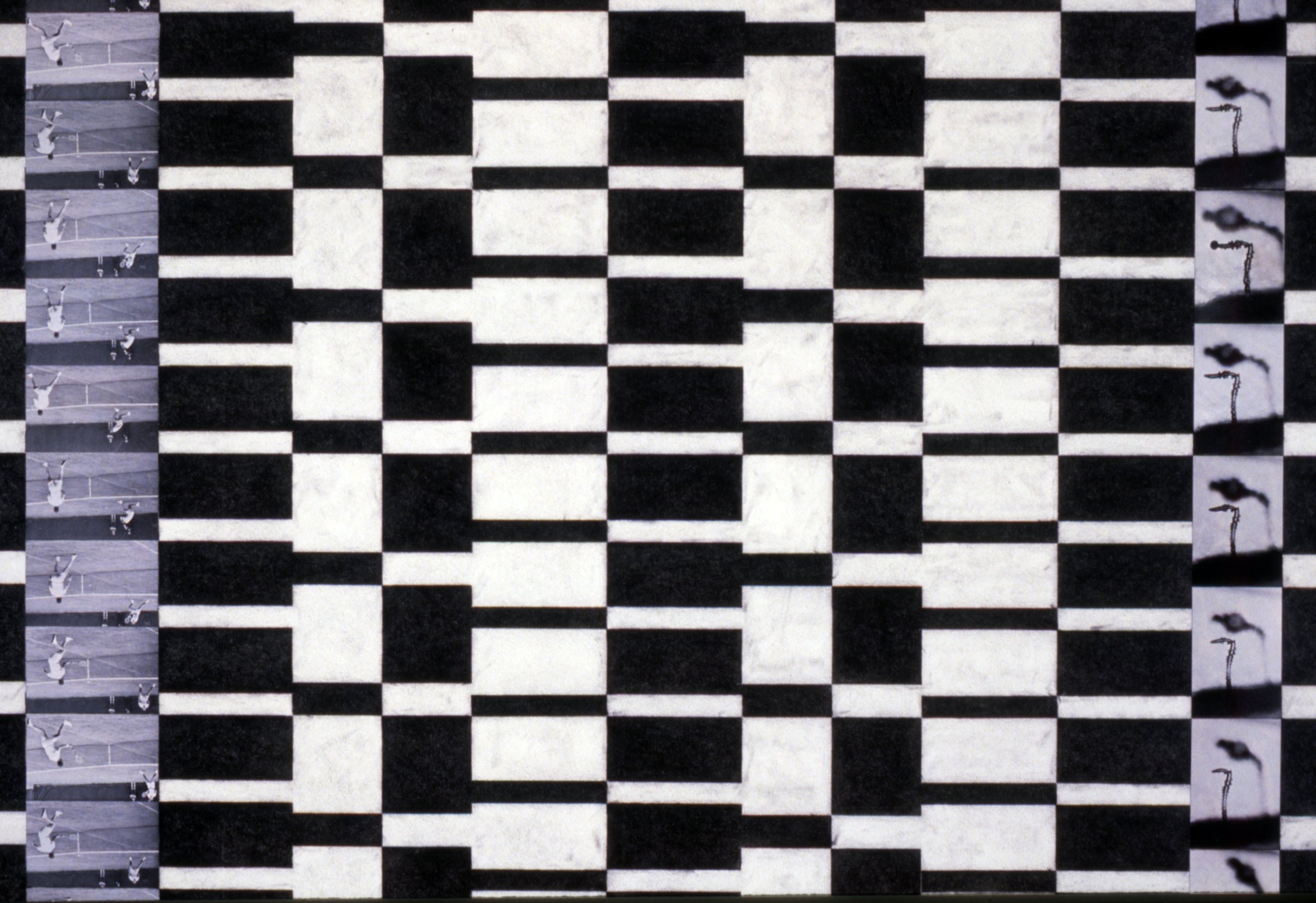

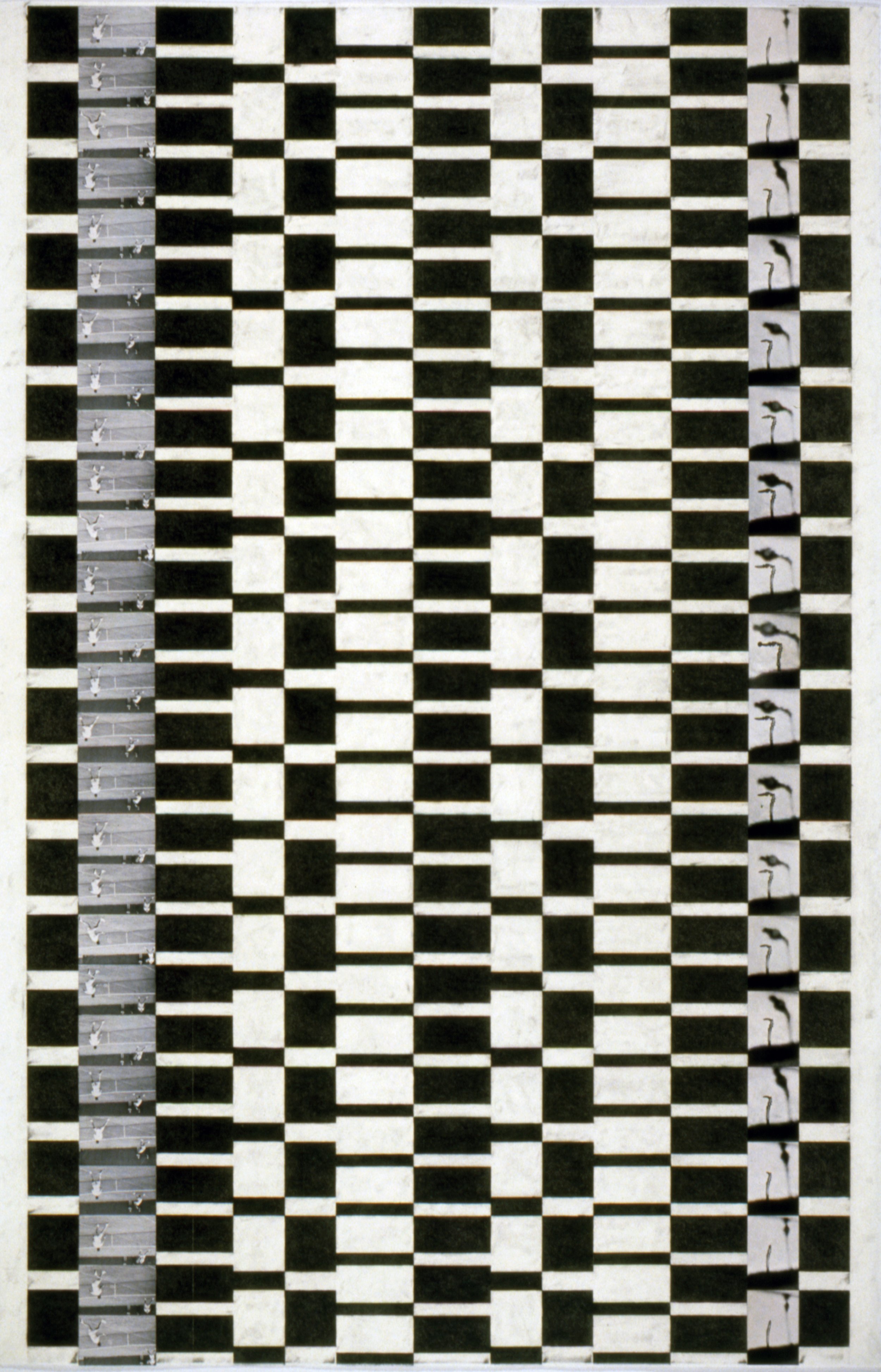

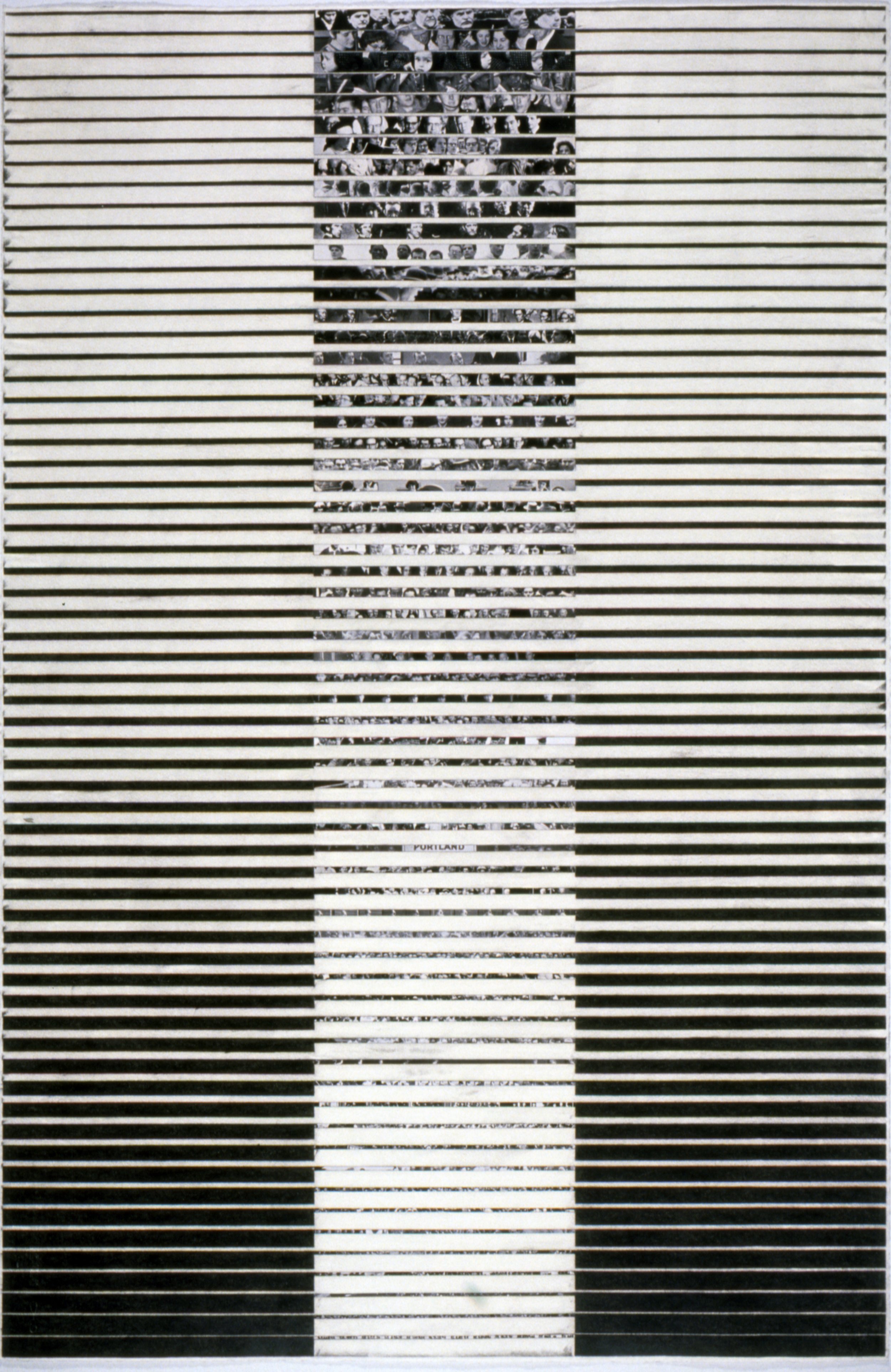

Even in the 1980s, when she was painting actors on television scenes in pixelated watercolors, Burleigh was experimenting with simulacra—copies of copies—that nonetheless appear “real.” She then began experimenting with old copies of Time Life Magazines, collaging repeating imagery onto paper which she then outlined in cascading black and white “treads.” The result is part op-art, part media-deconstruction, an homage to postmodernism via black and white nostalgia that feels like a glitch in the mainframe.

All of this coalesces in her most recent work Jealousy, an animation based on a novel of the same name by French writer and filmmaker Alain Robbe-Grillet. His literary style exemplified the nouveau Roman genre and encapsulated a so-called "theory of pure surface,” [3] in which a visceral response is extracted from the reader through a highly methodical, repetitious, and almost clinical description of objects alone. This approach has been compared to the process of psychoanalysis, which Carl Jung notably championed, and which sought to reveal unconscious truths through free association unencumbered by moral censorship (a liberation of the shadow archetype itself).

In Burleigh’s Jealousy, a 3D domestic rendering becomes the stage for a symphony of sinister sounds: turning gears, nocturnal wildlife, doors opening, closing, and opening again. As the viewer is led through a deserted home, awash in the artificial glow of incandescent light, objects are thrust into focus and (re)animated as if controlled by an omnipotent engineer.

The result is a simulacrum of the uncanny valley, a waking dream in a world so surreal, so unsettling, that the viewer is both seduced and repelled. It is the hyper-manifestion of our own collective unconscious. As Jean Baudrillard wrote, “The simulacrum is never that which conceals the truth—it is the truth which conceals that there is none. The simulacrum is true.” In other words, Burleigh’s art is so perfectly fake, it’s real—and if not now— then in the very near future.

Works cited

[1] Kimberly Burleigh, interview by the author, April 29, 2022.

[2] Jung, C. G. (Carl Gustav), 1875-1961. The Archetypes and the Collective Unconscious. [Princeton, N.J.] :Princeton University Press, 1980.

[3] Bruce Morrissette, “Surfaces and Structures in Robbe-Grillet’s Novels.” Preface to Alain Robbe-Grillet, Two novels by Robbe-Grillet: Jealousy and in the Labyrinth, New York: Grove Press, Inc., 1965, pg. 13.