Christopher Coleman: Excavating Humanity through Digital Art

By Halleta Alemu

Christopher Coleman’s work is a splashing geode of earth meeting technology. Traversing the globe, his work has been exhibited in more than 25 countries and diffuses through a collection of mediums, including sculpture, video, creative coding, and installation.

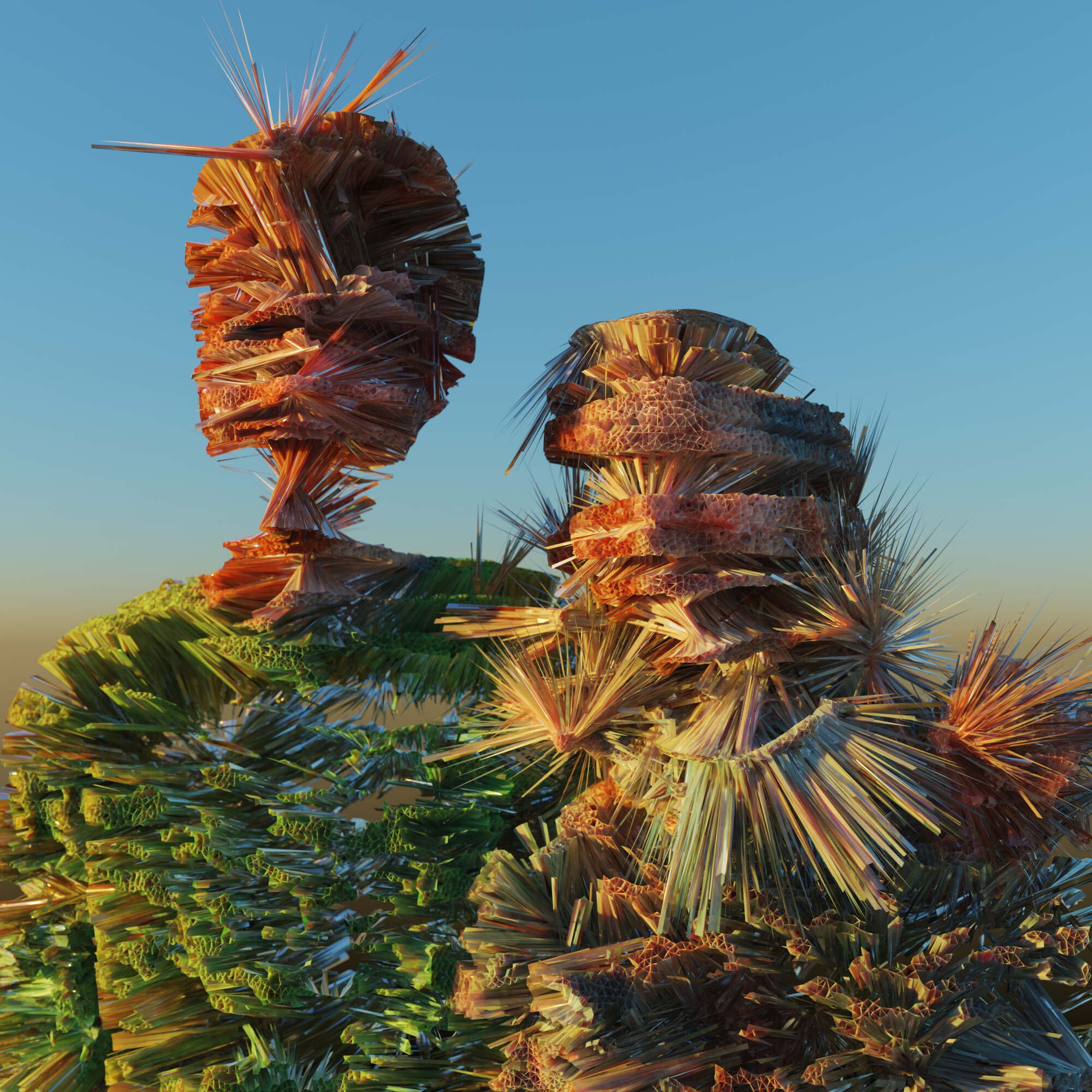

Most notably, his 3D scanning work is sublime. Using scans of various earth-dwelling things such as flowers, rock formations, and human beings, he weaves an extended reality through his vision. His GeoPortraits series marked a true test of intuitive skill and finesse. In this series, he took a set of unrecognizable 3D scans and, with specific time limits and content parameters, expanded upon each of them to transform their human likeness, resulting in a multimedia exploration of how one can capture a soul’s essence.

Coleman forms a bridge with his work, allowing us to question and look into our hybrid living state as both online and offline creatures. He inspires a harmonious balance, a middle ground where the question isn’t whether to be offline or online, but rather, where is the bridge that links the two? And how can we use each to develop ourselves and our communities further?

Community-mindedness is a large aspect of his practice. As a Professor of Emergent Digital Practices at the University of Denver and as the Director for the Clinic for Open Source Arts (COSA), Coleman is at the helm of ushering in our next generation of digital artists. After his own trials creating open-source software, he founded COSA to focus on nurturing the well-being of open-source software through a community-driven approach, creating an ecosystem of diversity, accessibility, and empowerment in the field of open-source tools. He is continuing this work with his new position as Professor of Art and Technology at The Ohio State University where he will also Direct the Advanced Computing Center for Arts and Design.

Coleman’s work marks a poetic foray into the unknown. In a world that is growing increasingly digital, it leaves us to wonder, where does our humanity lie in the scheme of it all? And what power do digital artists have in influencing the outcome? Below, Coleman tells us his answer, as well as what sparked his journey into digital art, why he considers 3D scanning to be an interesting failure, and the importance of referencing history.

The following interview has been edited for length and clarity.

Image of the artist, from DigitalColeman.com

You first studied sculpture and mechanical engineering in college. How did that form the basis of your work now?

I went to college to study mechanical engineering, and I think I imagined that I would be doing something creative. That I would take that knowledge and design toys, roller coasters, and really cool stuff. So, something more like product design would have been a really good match, but it didn’t exist in West Virginia at the time. This space between the sculptural and technical, solving technical challenges. But, there was no such thing. So, I studied mechanical engineering.

Then I talked to somebody who was going to graduate with their degree, and I asked, "What's the job actually like?" And he said, "Well, you know, nine to five, five days a week, I go into the office, and I engineer and reengineer the hook that goes on the end of the rod that opens and closes the Venetian blinds." And I said, "Oh, my God, I would kill myself."

You start to realize that every screw, every bolt, every attachment to every object is all mechanical engineering. So, the idea that I would get to do something grand and fun and inventive was not possible. I actually dropped out of school for a year to just, like, reckon with all of that.

Then, I went back to school and this time studied sculpture. This was the late '90s, and WVU, where I went to undergrad, had just added digital as a medium in the art department. Because I had extensive experience with computers, I was immediately attracted to try and figure out what exactly was this space. What did I want to do in digital? What did I want to do in sculpture? What are the spaces where they connect? Basically, ever since, I've been utilizing those skill bases together to make art.

Looking at your work, I see this mesh of earth diffusing through technology. It’s all at once very natural, yet very hyperreal. What’s your process in selecting a subject to 3D scan? And through the scanning process, what begins to reveal itself to you?

You know, it's different for different pieces. Certainly, right away when 3D scanning became possible, I understood it as a bridge between sculpting and my purely digital work, whether it was animation or something else. So, right away, scanning was revelatory and interesting. I’m still diving through it, but once you have a really deep understanding of scanning and how digital technology looks and thinks about those things you scanned, you realize simultaneously what a construct they are. The data you’ve supposedly gathered or the thing you’ve supposedly scanned—the scan is always a failure. Even a company that will sell you a $100,000 scanner that scans down to the millimeter will never fully simulate or replace the object or the person.

Scanning also involves time. I've always been interested in that failure, much like photography, where it used to be that if you wanted to take a photo, people would have to stand still for five minutes to get enough of an exposure. 3D scanning, a lot of times, is the same way. You're walking around a person, you're scanning them, but they're still living, breathing, and looking. They're in constant flux. So, the scan you get also contains time, not just their surface.

On some level, it's technical, but it's also deeply conceptual. I'm not interested in using a scan for a reproduction or true representation. I'm more interested in the scan as a kind of failure or facade. And I tie that into bigger ideas around capitalism, computing, and machine learning. All these things are tied up in that.

GeoPortraits #001-050++ courtesy of the artist

It's almost like scanning is a kind of memory of something. It will never be exactly what you saw; it will always be influenced and broken apart. Linking this to your GeoPortraits series, that project took my breath away. It surprised me how humanity can stretch into facets that I hadn't really thought of before. How did you decide on that idea?

So, the original set of scans, of which I have about 250, I took in Argentina during the 404 festival. I was invited there and essentially proposed a performance where I would be like a caricature artist, similar to those who sketch and exaggerate your features in a park or carnival. I wanted to take that notion and flip it on its head. I basically would 3D scan a person, set a timer for 10 minutes, and in that time, try to abstract them to the point of there being almost nothing recognizable left of them. Then I would print it out and put it on a board.

As people finished coming through the festival, they would swing back around and find their picture. In some ways, it was a study of who could recognize themselves once they were turned into nothing but 20 polygons. I was really interested in this sort of inversion of character and what kind of information we need to recognize even ourselves. I did this for about 250 people over three nights in Argentina. But that also meant that I had this giant bank of scans. However, I was also really cognizant of the fact that these are people with lives, and I've got some sort of strange version of their appearance stored on my hard drive. So, I thought a lot about respecting their privacy and respecting their data.

I did some portraits where I actually talked to the people and asked them to do so. This is like the SSH copy series. Those were much more direct conversations about using their appearance. But for this other series, the geo portrait series, I put forth my own one-a-day challenge, where I wanted to do a series of experiments quickly to iterate through a lot of different ideas. Every evening I would sit down and spend one to two hours doing another piece. What emerged were my memories of my interactions with each of these sets of people and my thoughts about the sort of energy they might have given off when they were scanned, at least during my brief interactions with them. Then I tried to extend that set of memories into the new portraits while, again, leaving them very unrecognizable.

What role do you think digital artists play in shaping how our world is growing more towards this integration of online and offline? How do you think digital artists can help us see ourselves and our societies differently?

I advocate all the time for the fact that the digital arts are, I don't want to say front lines, but we are the ones who are speaking through and with a lot of these technologies before they've been mainstreamed or as they're becoming mainstreamed. There's a huge amount of power in that. We're adept at speaking with these technologies, but there's also a huge danger with that.

When do you see some of the incoming challenges or dangers, and how do you help people see those in time for us to make a change before it's been mainstreamed to the point where it's too late? I feel a huge responsibility in that space. I think with some of the pieces I’ve done, they’re really an attempt to not just point at something and say, "Bad! Watch out, bad things!", but instead, as artists, actually propose ways to move forward. What does it actually look like to draw a new trajectory or a new pathway? Artists have a particular set of skills that they can apply to do that.

openFrameworks Education Summit, courtesy of the artist, summary article by Coleman can be found here.

Why was it important for you to start COSA? And why do you think it’s important that digital tools and software are free?

I made my own piece of open-source software a long time ago. I created something for a class to make teaching a little bit easier, and then I published it online because why not let other people use it. Then all of a sudden, you start getting support calls and feature requests. Suddenly, you're developing this piece of software that isn't just for your class but for classes all over the world. People are calling you because they're using it in their thesis projects or on stage during a concert. I picked up a collaborator, and we extended the software, but eventually, I stopped supporting it. It sort of turned into abandonware, which is the phrasing for it.

I went through the whole cycle and thought deeply about that experience. Knowing that there are thousands of pieces of software shared every day, many of them die on the vine and never get used by somebody else. But some of them become the primary tool for an artist to make something beautiful or powerful. You never know when a person in, say, Argentina, who doesn't have any money to buy Adobe software, really wants to speak to something they're facing but needs the tools to do it. Open source is such a valuable space for that.

37°11’30”N:105°25’46”E@2438m, courtesy of the artist

As a professor, aside from their access to more tools, what do you see in your students' mindsets that’s different from yours when you were their age?

When I was going to art school, if I wanted to see some amazing video art, even though I lived in West Virginia, like, if you live in New York City, you see digital art all the time, you go to a museum, whatever. But if you live in West Virginia, nobody's showing digital art. So, the only way that you would get to see these sorts of interesting things happening in the field is if you found a professor with a videotape or bootleg, a burned DVD of some performance or something. There was this real lack of being able to see the things that have come before and that would help inspire what you would do moving forward.

The beautiful thing is that now almost all of that is really available online. YouTube was invented, and artists have started sharing a lot of their work. Whether on Instagram or TikTok, you can follow the right accounts, and they're going to museums and taking good footage of the artwork. So, if you want to, you can find these things and see inspirational work.

But the problem is that nobody is. There is so much media and so much new stuff all the time, there's never a reason to watch anything old. So, I'm seeing students who haven't even watched something from a year ago. It seems weird for them to watch something that's old. They just don't see value in understanding where all of this cultural stack has come from. That's a huge challenge as teachers to say, "No, really, this was an important conversation, and here's how they tried to deal with it. And I know it's not the conversation you're having now, but you should learn from those lessons."

It's this beauty and travesty. Everything's available, but also everything's available. And the algorithm will never serve you anything that's old. It only serves you the new. It takes real effort to stop and say, "I'm gonna go watch something old."

Instagram: @digitalcoleman

Halleta Alemu is a multimedia writer whose work is an act of dissection – of zooming into the particles of reality to create new forms. Subscribe to her substack Electric Blue to read her poetic observations of the world.